Journal of Financial Planning: October 2023

Executive Summary

- Conventional financial planning wisdom surrounding municipal bonds suggests that as income increases, so should the likelihood of municipal bond investment (to offer legal tax avoidance and minimization). Municipal bonds are generally seen as a “safer” investment due to traditionally lower default rates. Thus, conventional wisdom would also suggest that as willingness to take financial risk decreases, the likelihood of municipal bond investment should increase. Because municipal bonds are a more specialized investment option (i.e., for tax minimization), their use should be associated with higher levels of financial knowledge. Relatedly, because municipal bonds are a more niche investment (compared to corporate stock, for example), their use should increase with use of a financial or other adviser.

- Using the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances, this study examines that conventional wisdom empirically and other aspects of municipal bond investment, including the associations between such ownership and professional investment advice.

- This study finds that municipal bond investment is positively associated with interest and dividend income, net worth, objective financial knowledge, and the use of a financial planner.

- It also finds that municipal bond investment is negatively associated with willingness to take financial risk.

-

Timothy M. Todd, Ph.D., is associate dean for faculty development and scholarship and professor of law at Liberty University School of Law.

Stuart Heckman, Ph.D., is a CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™ and an associate professor of practice and Ph.D. program director at Texas Tech University. His research focuses on professional financial planning and

on financial decisions involving uncertainty, especially among young adults and college students.

Maurice MacDonald, Ph.D., is a Kansas State University emeritus professor and teaches economics part-time at Boise State University. His scholarship spans from measures

of personal and family economic well-being and income adequacy, to intergenerational wealth transfer, to the economic status of children, college students, and the oldest old.

Municipal bond interest income is exempt from federal income taxation (U.S.C. § 103). Therefore, municipal bonds offer a tax advantage compared to similarly situated private-sector bonds. Conventional financial planning wisdom, then, suggests that as income increases, so should the likelihood of municipal bond investment (to offer legal tax avoidance and minimization). Moreover, municipal bonds are generally seen as a “safer” investment due to traditionally lower default rates (Cestau, Hollifield, Li, and Schürhoff 2019; Schwert 2017). Thus, conventional wisdom would also suggest that as willingness to take financial risk decreases, the likelihood of municipal bond investment should increase. Because municipal bonds are a more specialized investment option (i.e., for tax minimization), their use should be associated with higher levels of financial knowledge. Relatedly, because municipal bonds are a more niche investment (compared to corporate stock, for example), their use should increase with use of a financial or other adviser.

Despite these a priori assumptions about municipal bonds as an investment, there is a dearth of their actual examination in the financial planning literature. Therefore, this study advances the literature by exploring and empirically examining the conventional wisdom surrounding municipal bonds in the financial planning context.

Background

Historically, in the United States, municipal bonds span back to the early 1800s when the City of New York issued the first recorded municipal bond (Cestau, Hollifield, Li, and Schürhoff 2019). Today, the municipal bond market is a sizeable capital market in the United States; it has trillions in market capitalization and thousands of issuers (Cestau, Hollifield, Li, and Schürhoff 2019). Moreover, this market has grown with time; for example, in 1996, there was about $210 billion of municipal bonds issued—in 2016, that number grew to $450 billion (Cestau, Hollifield, Li, and Schürhoff 2019).

Investors can buy municipal bonds directly or through tax-exempt bond funds (Shamosh 2000). Some estimates indicate that households hold roughly 44 percent of state and local government tax-exempt debt directly (Galper, Rueben, Auxier, and Eng 2014). When indirect holdings are considered, too—such as through mutual funds and money-market funds—households account for another 28 percent of holdings (Galper, Rueben, Auxier, and Eng 2014). Together, then, households account for nearly 72 percent of tax-exempt bond holdings with banks, insurance companies, and other sources accounting for the balance (Galper, Rueben, Auxier, and Eng 2014).

Although a sizeable portion of municipal bond investors may be households, a relatively small number of households own municipal bonds (Bergstresser and Cohen 2016). Indeed, in their analysis using data from the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), Bergstresser and Cohen (2016) found that household ownership of municipal debt fell from 4.6 percent of households in 1989 to 2.4 percent in 2013. Moreover, they found an increasing concentration of municipal debt in more affluent households (Bergstresser and Cohen 2016). In particular, according to the 2013 Survey of Consumer Finances, 42 percent of all municipal debt was held by the top 0.5 percent wealthiest households—for comparison, this amount was 24 percent in 1989 (Bergstresser and Cohen 2016).

Municipal bonds have two key features. The first feature is a lower rate of default. Historically, municipal bond defaults are rare (Schwert 2017). Moreover, the default rates of rated municipal bond defaults are generally lower than rated corporate bonds (Cestau, Hollifield, Li, and Schürhoff 2019). Because of lower default rates and reduced risks, therefore, municipal bonds can offer a safer investment opportunity.

The second feature of municipal bonds is their unique tax advantage. For federal income tax purposes, gross income includes “all income from whatever source derived” (26 U.S.C. § 61). As the Supreme Court elucidated, Congress meant to exert “the full measure of its taxing power,” and income therefore consists of “undeniable accessions to wealth, clearly realized, and over which the taxpayers have complete dominion” (Commissioner v. Glenshaw Glass Co. 1955). Therefore, interest income is quintessential income. However, for a variety of policy reasons, Congress exempts certain income items from federal taxation—such as, for example, employer-provided health insurance (26 U.S.C. § 106), personal injury settlements (26 U.S.C. § 104), and certain discharges of indebtedness (26 U.S.C. § 108). One such exemption is that of interest from state and municipal bonds (U.S.C. § 103).

At the outset of the federal income tax, concerns arose about the federal government taxing state and local bond interest due to intergovernmental tax immunity (Glass 1946; Greenberg 2016; Richard 2017). Intergovernmental tax immunity refers to the concept that one sovereign cannot tax another sovereign because to do so would render one at the mercy of the other (Richard 2017). Indeed, this theme was manifested by Chief Justice John Marshall, who famously noted that “the power to tax involves the power to destroy” (McCulloch v. Maryland 1819). Alleviating these concerns, after the passage of the Sixteenth Amendment—expressly allowing the levy of a federal income tax—the Revenue Act of 1913 excluded municipal bond interest from taxation (Greenberg 2016). Section 103(a) provides the current tax exemption for municipal bonds by excluding from gross income interest on state and local bonds (26 U.S.C. § 103). However, if municipal bonds are traded on the secondary market, then that capital gain is taxed, just as with other property dispositions (26 U.S.C. § 1001)—even though municipal bonds’ interest income is excluded from federal gross income.

Despite the long vintage of the municipal-bond-interest income exclusion, however, some have questioned this policy choice. For example, Henry Simons, the famed American economist, advanced the idea that the federal tax exemption for municipal bond income was “a flaw of major importance” (Simons 1938, 172; Metcalf 1991). He argued that “[i]t opens the way to deliberate avoidance on a grand scale” (Simons 1938, 172). Moreover, the Treasury Department estimates the foregone revenue (i.e., tax expenditures) for the tax exemption of municipal bond interest to be more than $300 billion for fiscal years 2021 to 2030 (Treasury Department 2021). Naturally, then, there have been calls to eliminate the tax exemption for municipal bond interest income to broaden the income tax base (Poterba and Verdugo 2011).

Literature Review

Municipal bonds have two novel aspects as investment vehicles: First, they offer reduced taxation costs (because of the interest income being excluded from federal income taxes), and second, they offer reduced risk because of generally lower default rates. Thus, the tax benefits and risk attributes of municipal bonds are the focal points of our review.

Past literature has examined how taxation affects decision-making and even the pricing of investment vehicles. For example, Blaufus and Möhlmann (2014) demonstrated that investors exhibit tax-aversion bias, which refers to the “phenomenon that people may perceive an additional burden associated with tax payments compared to economically equivalent payments labeled differently” (p. 56). Therefore, investors may desire tax minimization even at the expense of net returns. Interestingly, they found that a tax deduction may be valued more highly than an equivalent tax exemption. This phenomenon, moreover, may explain in part the pricing of municipal bonds in secondary markets. Indeed, Ang, Bhansali, and Xing (2010) noted tax aversion as a rationale that high implicit tax rates are priced into the municipal bond market, although Kalotay (2016) argued that tax exemption of interest does not automatically confer tax-efficient returns.

The tax novelty of municipal bonds can also impact the ideal location in which to hold them. Shoven and Sialm (2003), for example, demonstrated that an optimal asset location (i.e., in what type of account an asset is placed), distinguished from allocation (i.e., the choice between different asset classes), improves the risk-adjusted performance of retirement savings. In particular, an optimal asset location calls for locating municipal bonds in taxable accounts if the effective tax rate of stocks is greater than the implicit tax rate for municipal bonds (Shoven and Sialm 2003).

As noted, rated municipal bonds generally have lower default rates than rated corporate bonds (Cestau, Hollifield, Li, and Schürhoff 2019). Thus, factors other than tax consequences may affect municipal bond investment. One factor may be attitudes toward risk. For example, Kriz (2004) found strong risk aversion or, alternatively, loss aversion in the municipal bond context. In other words, he found that the observed premium between municipal bonds and Treasury bonds cannot be explained through risk-neutral models—that is, a model in which risk-neutral investors evaluate risk-adjusted returns to a risk-free rate (Kriz 2004).

Another factor that may bear on municipal bond investment is the use of a professional adviser. Professional advisers—such as financial planners, accountants, and lawyers—regularly advise clients on tax and risk management. Consequently, the use of financial professionals may be associated with municipal bond investment because they advise in favor of a municipal bond investment or due to the increased levels of financial knowledge that they bring to the table (i.e., making the investor cognizant of the need for tax minimization). Professional advisers, such as accountants and financial planners, have sophisticated knowledge and are suited to help clients invest in those products when the need arises; these professionals may encourage a high-income client to invest in municipal bonds to offer a federal-income-tax-free income stream. Firms of professional advisers, moreover, also offer taxable-account separation for management efficiency. Financial professionals engaged in the investment or portfolio allocation process may recommend municipal bonds for a variety of reasons, such as reduced risk and interest income (in addition to the tax benefits).

Prior research has examined the benefits of financial advice, indicating generally that financial planners provide significant benefits (Seay, Kim, and Heckman 2016). In particular, working with a financial adviser is related to healthy financial behaviors, such as goal setting, diversification, and having an emergency savings fund (Kim, Pak, Shin, and Hanna 2018; Marsden, Zick, and Mayer 2011). Financial-adviser use has also been associated with better portfolio performance (Lei and Yao 2016), but the literature is mixed, with some studies indicating marginal benefits (Bergstresser, Chalmers, and Tufano 2009; Chalmers and Reuter 2012). On the other hand, do-it-yourself investors—relying on their own understanding—may make suboptimal decisions for myriad reasons, such as lack of knowledge and behavioral biases (Alyousif and Kalenkoski 2017).

Use of a financial planner is often viewed through the lens of help-seeking behavior (Grable and Joo 1999; Joo and Grable 2001). Prior research indicates that those who use financial advisers tend to have higher education levels, higher incomes, and more complicated financial situations (Salter, Harness, and Chatterjee 2010). Summarizing the literature, Alyousif and Kalenkoski (2017) noted “age, gender, wealth, income, home ownership, education, financial knowledge, confidence, risk tolerance, and negative life events as factors that influence the demand for financial advice” (p. 406). Nevertheless, although the proportion of households using financial planners has increased, planner use is still at a relatively low level (Hanna 2011). For example, a 2016 Northwestern Mutual study found that the majority of U.S. adults do not get professional financial advice (Northwestern 2016).

Personal financial knowledge and financial literacy may also be determinants of municipal bond investment. As Huston (2010) noted, financial literacy, financial knowledge, and financial education are often used synonymously. Broadly speaking, financial literacy is the ability to understand and manage one’s personal finances (Asaad 2015; Fan and Chatterjee 2017). Financial knowledge has been found to be positively associated with healthy financial behaviors and best practices (Robb and Woodyard 2011; Seay, Preece, and Le 2017). Interestingly, financial-adviser use may also impact a client’s financial literacy—in other words, clients learn from their interactions with their advisers (Balasubramnian and Brisker 2016). Financial knowledge and financial literacy may be related to municipal bond investment. As a person’s financial knowledge increases, so too should his or her ability to select investments that provide unique financial benefits (like reduced tax burdens).

Hypotheses

We empirically examined five hypotheses associated with municipal bond investment that are rooted in their federal income tax advantages, their reduced-risk benefits, and the investor’s or adviser’s investment and financial knowledge; all hypotheses were examined with control variables included. Because municipal bonds offer tax advantages compared to corporate bonds, we expected that, ceteris paribus, the tax advantage becomes more salient and coveted as income (and thus the marginal tax rate) increases. Therefore, our hypothesis about municipal bond investment and income (as a proxy for marginal tax rate) was as follows

Hypothesis 1: Municipal bond investment is positively associated with increases in income level.

Because state and local governments can raise revenue via the taxing power, municipal bonds may be seen as less risky because of a perceived lower default risk. Therefore, our hypothesis about municipal bond investment and willingness to take financial risk was this:

Hypothesis 2: Municipal bond investment is negatively associated with willingness to take financial risks.

Relatedly, because municipal bonds are more specialized and because more savvy investors know of their tax-minimization benefits, our hypotheses about municipal bond investment and financial knowledge—both subjective and objective—were these:

Hypothesis 3: Municipal bond investment is positively associated with subjective financial knowledge.

Hypothesis 4: Municipal bond investment is positively associated with objective financial knowledge.

We note several a priori rationales for why municipal bonds may be associated with professional advisers. First, municipal bonds are often associated with being a more specialized investment. Second, the professional adviser—such as a financial planner or accountant—may make express recommendations regarding legal tax minimization, such as suggesting municipal bonds. Third, professional advisers may be a critical source of information about a municipal bond investment. Therefore, our hypothesis about municipal bond investment and use of a professional adviser was this

Hypothesis 5: Municipal bond investment is positively associated with use of a professional adviser—such as a lawyer, accountant, or financial adviser.

Methodology

Data

This study used data from the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF). The SCF, a cross-sectional survey of households in the United States, provides comprehensive financial information and demographic characteristics. The public version of the 2019 SCF reported data from 5,777 households using a complex sample design that oversampled wealthy households. The SCF uses multiple imputation to protect privacy and eliminate missing data (Federal Reserve 2022). In addition to demographic data, the SCF also has robust household financial data, including data about various investments, including municipal bonds. Additionally, the SCF also asks questions about information sources used for saving and investment decisions, including financial-adviser use, which is an examined hypothesis in this study. Past literature has used the SCF when examining various aspects of financial-planner use (Heckman, Seay, Tae Kim, and Letkiewicz 2016) and in investigating municipal bond use (Bergstresser and Cohen 2016).

Because the hypotheses here are focused on active investment decisions (i.e., to hold municipal bond investments), the sample in the study was restricted to those households with investment assets, which was defined as having stock, bond, or mutual fund investments (excluding money-market mutual funds).1 Our analytical sample contained 1,822 households.

Model

Logistic regression was used to determine factors associated with investments in municipal bonds. The model is expressed as:

where pi represents the probability of household i having a municipal bond investment (i.e., yi = 1), b represents a vector of estimated coefficients (including an intercept), and x represents a vector of variables (Allison 2012). In addition to the logistic coefficients, odds ratios are presented, which represent the respective exponentiated coefficient. Odds ratios allow a more meaningful way to interpret the measure of association between variables in a logistic regression (Hosmer, Lemeshow, and Sturdivant 2013). For a particular variable, an odds ratio greater than 1.0 means that the odds of municipal bond investment are greater with changes in the respective variable; on the other hand, an odds ratio of less than 1.0 means that the odds of municipal bond investment are lower with changes in the variable.

Moreover, we model our logistic model sequentially, presenting three models. The first model consists of demographic controls only. The second model incorporates types of income, net worth amounts, and the demographic controls. The third (and full) model adds financial attitudes (e.g., risk willingness) and adviser use. A benefit to this sequential approach is to examine coefficient stability across sequential specifications.

Due to the SCF’s multiple imputation structure, Lindamood, Hanna, and Bi (2007) recommended using all five implicates with repeated-imputation inference (RII) to obtain more accurate variance estimates and significance levels. To account for the complex sample design, a bootstrapping method was used to adjust for a household’s unequal probability of selection (Nielsen and Seay 2014). Shin and Hanna (2017), however, posited that ignoring complex sample design will not make much difference in many models. Nevertheless, we used repeated-imputation inference and accounted for the complex sample design by bootstrapping standard errors (with 999 bootstrap samples).2

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable in this study was a binary variable that indicated whether a household had a municipal bond investment—either directly or as part of a tax-free bond mutual fund or exchange-traded fund (coded 1) from those who did not (coded 0). Across all five implicates, there were 2,351 municipal-bond-investing households (for an average of 470 per implicate).3

Independent Variables 4

Because of the relatively small number of households that reported investments in municipal bonds (about 470 households), demographic and control variables were carefully considered for combination to improve model performance and to prevent data sparseness across cells. Demographic variables include age (coded as a continuous variable, and we included an age-squared term for potential non-linear age effects);5 race (White or non-White); marital status (coded as 1 if the reference person was married or living with a partner); gender; education (categorical); number of children; occupational status; and homeownership status.

Not all income is necessarily taxed similarly (e.g., net capital gain may be taxed at preferential rates), and the decision to invest in municipal bonds may be related to the source, amount, and taxation of various types of income. Consequently, income was broken into several variables. Wage income was defined as the annual income from wages and salaries. Interest and dividend income was defined as income from non-taxable investments (like municipal bonds), other interest, and dividends. Capital gain income was defined as net annual income from gains or losses in mutual funds, stocks, bonds, or real estate. Social Security and retirement income was defined as net income from Social Security, pensions, annuities, and disability or retirement programs. Business, self-employment, and farm income was defined as net annual income from a sole proprietorship, farm, other businesses, or rent. Transfer payments or other income was defined as annual income from unemployment, worker’s compensation, child support or alimony, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and other sources. In addition, net worth was also included.

All amounts were based on calendar year 2018 and were inflation adjusted to 2019 dollars as provided in the public Federal Reserve data. Generally, a natural log transformation is useful to handle skewed distributions (Lee and Kim 2016), and household wealth data is generally skewed (Friedline, Masa, and Chowa 2015). However, natural log transformations are defined only for positive amounts; consequently, they are not helpful for various income or wealth measures, which may contain zeros or negative values. Therefore, instead of natural log transformations to handle the negative values of net worth and other zero values, we used an inverse hyperbolic sine transformation for the income and net-worth variables (Friedline, Masa, and Chowa 2015; Lee and Kim 2016).

The inverse hyperbolic sine (IHS) transformation can be used with or without a scale parameter, referred to as theta (q). The scale parameter can be used to affect the proportion of the function’s x-values (the domain) that is essentially linear (Pence 2006). Scale parameters are often used when the IHS-transformed variable is a dependent variable (Friedline, Masa, and Chowa 2015). Without an expressly defined scale parameter (i.e., q = 1), the IHS transformation is defined as:

where x represents the variable to be transformed (Friedline, Masa, and Chowa 2015; Lee and Kim 2016). Past literature has noted several benefits of using the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation. As noted by Friedline, Masa, and Chowa (2015), for example, these benefits include adjusting for skewness, allowing for zero and negative values, and, when included as an independent variable, its interpretation is like that of the natural log transformation.

Lusardi and Mitchell (2014) noted three core competencies for financial literacy: (1) numeracy and capacity to do calculations (e.g., related to interest rates), (2) an understanding of inflation, and (3) an understanding of risk and diversification. The three SCF financial literacy questions track these competencies. First, the SCF asks about the risks associated with single-stock ownership versus mutual-fund ownership. Second, it asks a question about compound interest. Third, it asks a question about the interaction between inflation and purchasing power. We therefore coded objective financial knowledge as the sum of the correct answers to these three questions.

The SCF asks about information sources used for savings and investment decisions, including the use of accountants, lawyers, and financial planners. Measuring household use of financial planners is fraught with challenges (see Heckman, Seay, Tae Kim, and Letkiewicz 2016). In the SCF, households can select up to 15 sources of information used for saving and investment decisions. For our purposes, we coded households as using an accountant, lawyer, or financial planner if they selected the respective professional among their listed information sources; selections were not mutually exclusive (e.g., a household could be coded as 1 for both accountant and financial-planner use).

Related to the role of advisers as information sources, which may bear on the decision to invest in municipal bonds, past literature has also explored the factors associated with investment-information search generally (e.g., Lin and Lee 2004). These factors include subjective knowledge and risk tolerance (Lin and Lee 2004). Consequently, we also included various financial attitudes. Subjective financial knowledge was coded as a continuous variable (maximum of 10) on the respondent’s self-reported knowledge about personal finance. Because investors may select municipal bonds due to their lower default rates, we also included a variable about willingness to take financial risks, which was coded as a continuous variable (maximum of 10).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

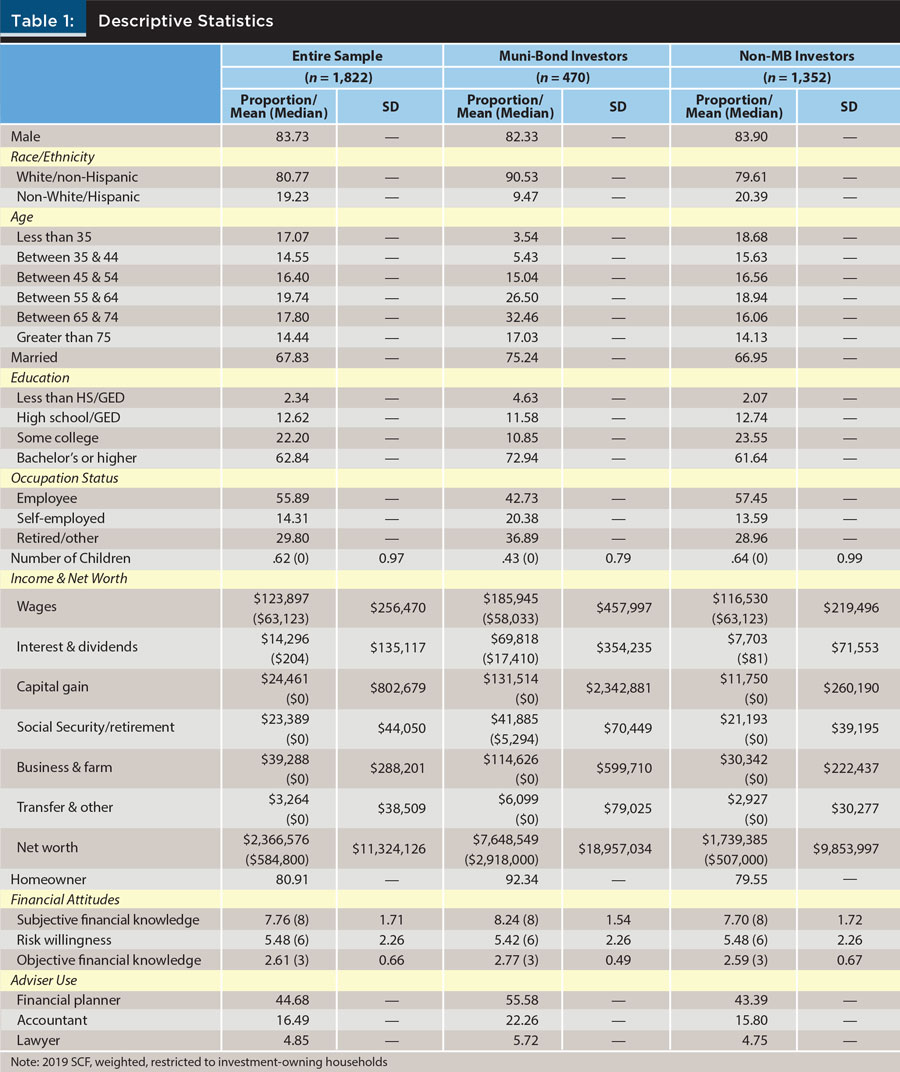

As noted, our analytical sample contained 1,822 households. The descriptive statistics for the full analytical sample, as well as broken out for those who had and did not have municipal bond investments, are presented in Table 1.6

A majority of our sample was married (67.83 percent), college educated (62.84 percent), and homeowners (80.91 percent). Age brackets were distributed relatively evenly, and a majority of the sample were employees (55.89 percent). The skew in various sources of income is evident, with most sources of income having a median of $0 but larger mean values. The sample also has a median net worth of $584,800, which is noteworthy.

Considering the demographic difference between municipal bond investors and those without municipal bond investments, we see that a greater proportion of those not invested in municipal bonds are non-White (20.39 percent compared to 9.47 percent) and that municipal bond investors tend to be concentrated in older households, with less than 25 percent of municipal-bond-holding households being younger than 54 years old (whereas those same age brackets constitute about 50 percent of the non-municipal bond households). Municipal bond households also reported higher levels of four-year college degrees (72.94 percent versus 61.64 percent). Municipal bond households also reported higher levels of each source of income and overall net worth. Also, we see that municipal bond households reported higher levels of adviser use across each type of adviser.

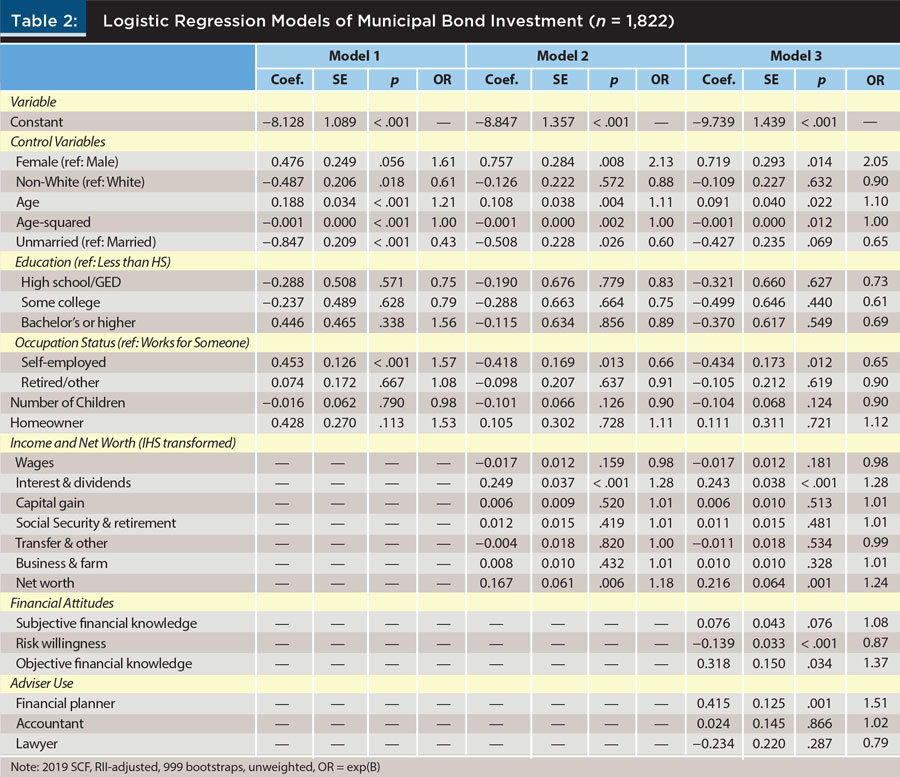

Next, we examined the logistic regression model, the results of which are reported in Table 2; we discuss each model in turn.

In the first model, which contained demographic controls only, we observe a few significant controls, namely race, age, marital status, and being self-employed. In this first model, households with a respondent who reported being non-White had reduced odds of municipal bond investment (OR = 0.61, p = .018); however, as discussed below, this significance disappeared in later models. Those households with an unmarried reference person also had reduced odds of municipal bond investment (OR = 0.43, p = .000). Age was positively associated with municipal bond investment (OR = 1.21, p = .000), and although the age-squared term was significant, its magnitude was not. Curiously, being self-employed resulted in increased odds of municipal bond investment in this first model (OR = 1.57, p = .000).

In the second model, which incorporated income and net worth levels, race was no longer significant. Gender was now significant, with households with female reference persons indicating increased odds of municipal bond investment (OR = 2.13, p = .008). Age was still positively associated with municipal bond investment (OR = 1.11, p = .004). Self-employment status was still significant, but the direction changed (OR = 0.66, p = .013). We see two variables of significance in the financial controls. First, interest and dividend income was positively associated with municipal bond investment (OR = 1.28, p = .000). Second, net worth was positively associated with municipal bond investment (OR = 1.18, p = .006).

The results of the third (and full) model, which incorporated financial attitudes and adviser use, showed several significant associations related to municipal bond investments. Like with the second model, we observed a gender effect, with female-headed households having increased odds of municipal bond investment (OR = 2.05, p = .014). We still observe a positive age association (OR = 1.10, p = .022); the age-squared term still is relatively small in magnitude. Next, we still see the negative relationship between self-employment status and municipal bond investment (OR = 0.65, p = .012). Like in the second model, there is still a positive relationship between interest and dividend income and municipal bond investment (OR = 1.28, p = .000). Similarly, there is a positive relationship between net worth and municipal bond investment (OR = 1.24, p = .001).

There are also significant relationships with the financial attitudes and adviser-use variables in the third model. There is a negative relationship between risk willingness and municipal bond investment (OR = 0.87, p = .000). There is a positive relationship between objective financial knowledge and municipal bond investment (OR = 1.37,p = .034). With respect to adviser use, we observed a positive relationship between financial-planner use and municipal bond investment (OR = 1.51, p = .001). Notably, none of the other adviser-use variables were significant.

Discussion

Hypothesis 1 posited a relationship between municipal bond investment and income level. This relationship was based on the belief that as a household’s wage and other income increased—presumably along with higher marginal income-tax brackets—tax-free municipal bond income would become more attractive. In other words, tax minimization becomes more desired. However, we found an association only between dividend and interest income and municipal bond investment, which is not necessarily surprising because municipal bond ownership gives rise to interest income. The lack of income associations could have been muddied by the breakdown of income into constituent parts. To test this, we estimated Model 3 including total income (inverse hyperbolic sine transformed), instead of its constituent parts as presented; in this case, however, income did not have a significant association with municipal bond investment (OR = 0.99, p = .886). Thus, we did not find general support for Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 2 posited a negative relationship between willingness to take financial risks and municipal bond investment. We found support for this hypothesis. In Model 3, risk willingness was negatively associated with municipal bond investment (OR = 0.87, p = .000). In other words, as willingness to take financial risks increased, the odds of municipal bond investment decreased. This finding is relevant for advisers who need to pair investment and portfolio allocations with a client’s risk tolerance. Municipal bond investments can provide a way to cater to those reduced levels of risk willingness while at the same time providing a tax advantage to clients.

Hypotheses 3 and 4 posited positive relationships between subjective and objective financial knowledge, respectively. Subjective financial knowledge was not significant in Model 3, thus indicating no support for Hypothesis 3. However, objective financial knowledge (the financial literacy questions) did have a positive association in Model 3 (OR = 1.37, p = .034), indicating support for Hypothesis 4.

Hypothesis 5 posited a positive relationship between using a professional adviser and municipal bond investment. We examined advisers that are traditionally associated with investment advice or tax advice, namely financial planners, accountants, and lawyers. We found support in part for this hypothesis. In Model 3, using a financial planner was positively associated with municipal bond investment (OR = 1.51, p = .001). This result comports with the conventional wisdom. Financial planners can recommend or manage a client’s tax strategies; thus, the presence of professional financial advice increases the likelihood of standard tax-minimization advice, such as selecting tax-preferred investments like municipal bonds. Interestingly, with this model, a financial planner was the only professional adviser significantly associated with municipal bond investment. Indeed, even after controlling for risk willingness, financial knowledge, and other control variables, those using a financial adviser were more likely to have municipal bond investments; this suggests a possible recommendation effect.

In short, this study suggests that differences exist between those who invest in municipal bonds and those who do not. Not only are they different in demographic and financial-profile information based on the demographic statistics, but they also differ in more subtle ways, such as willingness to take financial risks and use of professional advisers. One salient implication for financial planners is to focus not only on the client’s financial information, but also on their intangible characteristics, such as willingness to take financial risks.

Although we did not observe general income (and wage income) associations, the positive relationship between sources of some investment income (e.g., interest and dividend income) and municipal bond investment may indicate smart income tax planning. Some sources of income cannot readily be shifted or minimized (such as active wage income). Indeed, the same is true for the other sources of passive income, such as Social Security income, which are often fixed by some external source or formula, regardless of tax consequences. Some sources—like investment income—can be tax shifted by selecting tax-preferred investments, like municipal bonds.

This is particularly relevant given that municipal bond investment was positively related to financial-planner use. When a client’s investment income increases, advisers should be sure to consider income-tax-free sources of investment income to minimize taxes to the extent possible. Such planning not only helps the client, but also reinforces the value proposition of using a paid professional with specialized training. Indeed, this is reinforced with the inclusion of financial-knowledge variables in the model. Even when we controlled for financial knowledge, we found that those using a financial planner were still more likely to have municipal bond investments. This indicates, potentially, that the inclusion of municipal bonds in the portfolio is not due to the client’s own financial knowledge, but rather due to the advice of the financial planner. Indeed, more research should be conducted in this vein. Similarly, advisers can use the conclusions of this study—that increases in some sources of investment income, increases in net worth, and decreases in levels of willingness to take financial risks lead to increased likelihood of municipal bond investments—as a screening mechanism or heuristic for filtering clients who may benefit from a municipal bond investment strategy.

Limitations

The number of households with a municipal bond investment was small in the 2019 SFC (i.e., about 475 out of 5,777 households, or less than 9 percent of the full SCF). With the sample restricted to investment-owning households, municipal bond holders constituted about 25 percent of the analytical sample. Nevertheless, to minimize the effect of the overall small number of municipal-bond-investing households and to prevent data sparseness across cells, we kept our model simple. Thus, due to that simplicity and parsimony, we may not have captured or controlled for all relationships or confounders.

Moreover, to account for possible cell sparseness, we examined a logistic model using Firth’s penalized likelihood correction as a robustness check (Todd and Seay 2021). We ran the Firth models on an implicate-by-implicate basis (without bootstrapping); across each implicate, the variables of interest—namely net worth, risk willingness, financial-planner use, and interest and dividend income—were similar in magnitude and significance to the Model 3 results.

There are also potential timing issues with our measure of financial-planner use. Given that the data is cross-sectional, we are unsure whether the use of a financial adviser (or other professional) preceded the municipal bond investment. It is possible that those investments were purchased before the input of a financial professional. Also, just because a household generally uses a financial adviser or other professional for savings and investment decisions does not mean that an adviser was used for the decision about the municipal bond investment. Similarly, the SCF has no measure of the efficacy or usefulness of the professional advice given. Although we model the presence of municipal bond investment, there is naturally heterogeneity and differences within the municipal bond asset class that our model does not account for. Lastly, as with any secondary data set, there is a risk of self-report error.

Conclusion

In sum, the conventional wisdom surrounding municipal bond investors is largely true—that is, such bonds can be used to shield interest and dividend income from taxation, which is emblematic of smart and legal tax minimization. Municipal bonds are generally safer, with a lower default rate compared to corporate bonds, so those with a higher willingness to take financial risks were less likely to invest in them. Further, they tend to be used by those with higher net worth and higher levels of financial knowledge. Moreover, the use of a financial planner is associated with an increased likelihood of having a municipal bond investment, indicating that advisers may steer their clients into municipal-bond-based strategies.

Municipal bonds are a valuable and important tool for financial planners. The conventional wisdom posits that municipal bonds are ideal in several instances, namely surrounding risk reduction and tax minimization. Financial advisers should continue to evaluate the benefits of municipal bond investments in these situations. An ideal time to broach the topic around municipal bond investment—and highlights one of their main advantages—is during tax planning with the client, particularly if reallocating invested assets would result in a lowered marginal tax bracket. As well, municipal bond investment can also be an important part of the retirement-income planning discussion because the reduced default risk and steady income are particularly salient in this phase of the financial planning life cycle.

Citation

Todd, Timothy M., Stuart Heckman, and Maurice MacDonald. 2023. “Examining the Conventional Wisdom of Municipal Bond Investments and Use in Financial Planning.” Journal of Financial Planning 36 (10): 66–82.

Endnotes

- Other data cleaning included removing observations with certain financial values reported as “−9,” which represent negative values not reported in the public data file.

- We used the scfcombo package for STATA (Nielsen 2015; Pence 2015).

- The number of municipal bond holders varied across implicates.

- When possible, to improve reproducibility, coded variables were used directly from the Federal Reserve SCF macro.

- In our descriptive statistics table, we present age as a categorical variable so readers can see the stratification of age between those who do and do not own municipal bonds.

- The number of municipal bond households vary by implicate; consequently, n amounts are rounded for the subgroup columns in Table 1.

References

26 U.S.C. § 61.

26 U.S.C. § 103.

26 U.S.C. § 104.

26 U.S.C. § 106.

26 U.S.C. § 108.

26 U.S.C. § 1001.

Allison, Paul. 2012. Logistic Regressing Using SAS: Theory and Application. 2nd ed. Cary: SAS Institute, Inc.

Alyousif, Mayer, and Charlene Kalenkoski. 2017. “Who Seeks Financial Advice?” Financial Services Review 26 (4): 405–432.

Ang, Andrew, Viner Bhansali, and Yuhang Xing. 2010. “Taxes on Tax-Exempt Bonds.” The Journal of Finance 65 (2): 565–601.

Asaad, Colleen. 2015. “Financial Literacy and Financial Behavior: Assessing Knowledge and Confidence.” Financial Services Review 24 (2): 101–117.

Balasubramnian, Bhanu, and Eric Brisker. 2016. “Financial Adviser Users and Financial Literacy.” Financial Services Review 25 (2): 127–155.

Bergstresser, Daniel, John Chalmers, and Peter Tufano. 2009. “Assessing the Costs and Benefits of Brokers in the Mutual Fund Industry.” Review of Financial Studies 22 (10): 4129–4156.

Bergstresser, Daniel, and Randolph Cohen. 2016. “Changing Patterns in Household Ownership of Municipal Debt.” The Brookings Institution.

Blaufus, Kay, and Axel Möhlmann. 2014. “Security Returns and Tax Aversion Bias: Behavioral Responses to Tax Labels.” Journal of Behavioral Finance 15 (1): 56–69.

Cestau, Dario, Burton Hollifield, Dan Li, and Norman Schürhoff. 2019. “Municipal Bond Markets.” Annual Review of Financial Economics 11 (1): 65–84.

Chalmers, John, and Jonathan Reuter. 2012. “Is Conflicted Investment Advice Better Than No Advice?” NBER Working Paper No. 18158. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. www.nber.org/papers/w18158.

Commissioner v. Glenshaw Glass Co., 348 U.S. 426. 1955.

Fan, Lu, and Swarn Chatterjee. 2017. “Borrowing Decisions of Households: An Examination of the Information Search Process.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 28 (1): 95–106.

Federal Reserve. 2022. “Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF).” www.federalreserve.gov/econres/scfindex.htm.

Friedline, Terri, Rainier Masa, and Gina Chowa. 2015. “Transforming Wealth: Using the Inverse Hyperbolic Sine (IHS) and Splines to Predict Youth’s Math Achievement.” Social Science Research 49: 264–287.

Galper, Harvey, Kim Rueben, Richard Auxier, and Amanda Eng. 2014. “Municipal Debt: What Does It Buy and Who Benefits?” National Tax Journal 67 (4): 901–924.

Glass, Carter. 1946. “A Review of Intergovernmental Immunities from Taxation.” Washington and Lee Law Review 4 (1): 48–68.

Grable, John, and So-Hyun Joo. 1999. “Financial Help-Seeking Behavior: Theory and Implications.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 10 (1): 14–25.

Greenberg, Scott. 2016, July 21. “Reexamining the Tax Exemption of Municipal Bond Interest.” Tax Foundation. https://taxfoundation.org/reexamining-tax-exemption-municipal-bond-interest.

Hanna, Sherman. 2011. “The Demand for Financial Planning Services.” Journal of Personal Finance 10 (1): 36–62.

Heckman, Stuart, Martin Seay, Kyoung Tae Kim, and Jodi Letkiewicz. 2016. “Household Use of Financial Planners: Measurement Considerations for Researchers.” Financial Services Review 25 (4): 427–446.

Hosmer, David, Stanley Lemeshow, and Rodney Sturdivant. 2013. Applied Logistic Regression. 3rd ed. Hoboken: Wiley.

Huston, Sandra. 2010. “Measuring Financial Literacy.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 44 (2): 296–316.

Joo, So-Hyun, and John Grable. 2001. “Factors Associated with Seeking and Using Professional Retirement-Planning Help.” Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 30 (1): 37–63.

Kalotay, Andrew. 2016. “Tax-Efficient Trading of Municipal Bonds.” Financial Analysts Journal 72 (1): 48–57.

Kim, Kyoung, Tae-Young Pak, Su Shin, and Sherman Hanna. 2018. “The Relationship Between Financial Planner Use and Holding a Retirement Saving Goal: A Propensity Score Matching Analysis.” Financial Planning Review 1 (1–2): e1008.

Kriz, Kenneth. 2004. “Risk Aversion and the Pricing of Municipal Bonds.” Public Budgeting & Finance 24 (2): 74–87.

Lei, Shan, and Rui Yao. 2016. “Use of Financial Planners and Portfolio Performance.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 27 (1): 92–108.

Lee, Jae, and Kyoung Tae Kim. 2016. “The Role of Propensity to Plan on Retirement Savings and Asset Accumulation.” Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 45 (1): 34–48.

Lin, Qihua, and Jinkook Lee. 2004. “Consumer Information Search When Making Investment Decisions.” Financial Services Review 13 (4): 319–332.

Lindamood, Suzanne, Sherman Hanna, and Lan Bi. 2007. “Using the Survey of Consumer Finances: Some Methodological Considerations and Issues.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 41 (2): 195–222.

Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia Mitchell. 2014. “The Economic Importance of Financial Literacy: Theory and Evidence.” Journal of Economic Literature 52 (1): 5–44.

McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 316. 1819.

Marsden, Mitchell, Cathleen Zick, and Robert Mayer. 2011. “The Value of Seeking Financial Advice.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 32 (4): 625–643.

Metcalf, Gilbert. 1991. “The Role of Federal Taxation in the Supply of Municipal Bonds: Evidence from Municipal Governments.” National Tax Journal 44 (4): 57–70.

Nielsen, Robert. 2015. “SCF Complex Sample Specification for Stata.” Department of Financial Planning, Housing, and Consumer Economics, University of Georgia, Athens, GA. www.researchgate.net/publication/291814973_SCF_Complex_Sample_Specification_for_Stata.

Nielsen, Robert, and Martin Seay. 2014. “Complex Samples and Regression-Based Inference: Considerations for Consumer Researchers.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 48 (3): 603–619.

Northwestern Mutual. 2016. “2016 Planning and Progress Study.” https://news.northwesternmutual.com/planning-and-progress-study-2016.

Pence, Karen. 2006. “The Role of Wealth Transformations: An Application to Estimating the Effect of Tax Incentives on Saving.” Contributions in Economic Analysis & Policy 5 (1).

Pence, Karen. 2015. “SCFCOMBO: Stata Module to Estimate Errors Using the Survey of Consumer Finances.” EconPapers. https://econpapers.repec.org/software/bocbocode/s458017.htm.

Poterba, James, and Arturo Verdugo. 2011. “Portfolio Substitution and the Revenue Cost of the Federal Income Tax Exemption for State and Local Government Bonds.” National Tax Journal 64: 591–614.

Richard, Kyle. 2017. “Towards a Standard for Intergovernmental Tax Immunity Between the Several States.” Tax Lawyer 70: 869–905.

Robb, Cliff, and Ann Woodyard. 2011. “Financial Knowledge and Best Practice Behavior.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 22 (1): 60–70, 86–87.

Salter, John, Nathaniel Harness, and Swarn Chatterjee. 2010. “Utilization of Financial Advisors by Affluent Retirees.” Financial Services Review 19 (3): 145–263.

Schwert, Michael. 2017. “Municipal Bond Liquidity and Default Risk.” The Journal of Finance 72: 1683–1722.

Seay, Martin, Kyong Tae Kim, and Stuart Heckman. 2016. “Exploring the Demand for Retirement Planning Advice: The Role of Financial Literacy.” Financial Services Review 25 (4): 331–350.

Seay, Martin, Gloria Preece, and Vincent Le. 2017. “Financial Literacy and the Use of Interest-Only Mortgages.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 28 (2): 168–180.

Shamosh, Michael. 2000. “Has the Time Passed for Municipal Bond Funds?” Journal of Financial Planning 13 (8): 116–124.

Simons, Henry. 1938. Personal Income Taxation. University of Chicago Press.

Shin, Su Hyun, and Sherman Hanna. 2017. “Accounting for Complex Sample Designs in Analyses of the Survey of Consumer Finances.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 51 (2): 433–447.

Shoven, John, and Clemens Sialm. 2003. “Asset Location in Tax-Deferred and Conventional Savings Accounts.” Journal of Public Economics 88: 23–38.

Todd, Timothy, and Martin Seay. 2021. “Financial Attributes, Financial Behaviors, Financial-Advisor-Use Beliefs, and Investing Characteristics Associated with Having Used a Robo-Advisor.” Financial Planning Review 3 (3): e1104.

Treasury Department. 2021. “Tax Expenditures.” https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/Tax-Expenditures-FY2022.pdf.